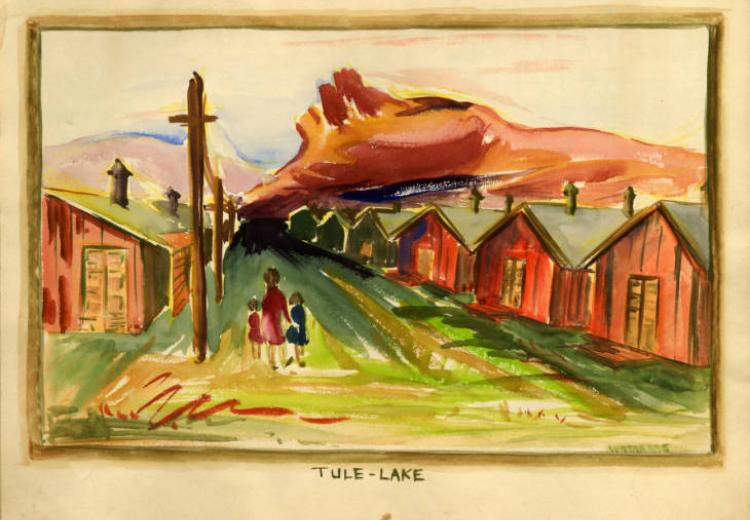

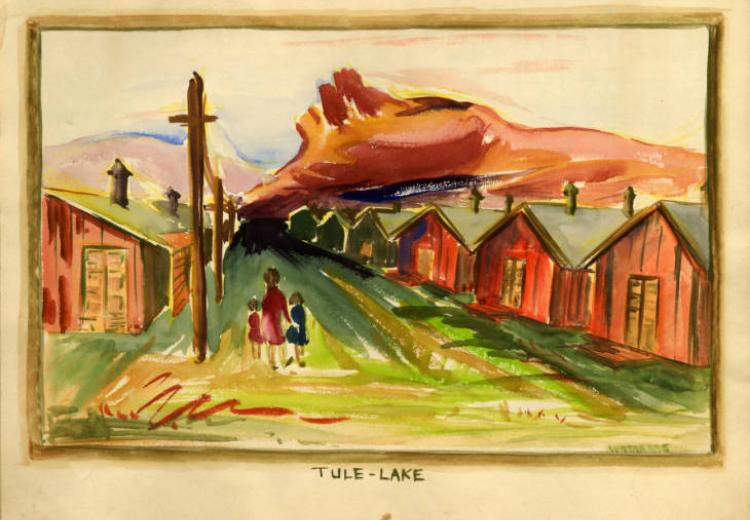

Watercolor painting depicting three figures, two children and one adult, walking towards a road lined with barracks and electrical poles (Tule Lake, 1942).

This lesson examines the incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry during WWII. Students will analyze primary sources to learn about the consternation caused by the questionnaire that was used to determine the loyalty of the Japanese and Japanese Americans incarcerated in War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps, and the subsequent removal of “disloyals” to the Tule Lake Segregation Camp.

What did loyalty mean to Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during WWII?

What powers should a President have during a time of war?

What is the legacy of the Japanese American internment camps?

Examine the motives for moving Japanese Americans to interment camps during WWII.

Analyze the complexity of life experienced by Japanese Americans incarcerated in Tule Lake and other internment camps.

Analyze archival documents to determine the consequences of incarcerating Japanese Americans during a time of war.

Evaluate the legacy of the internment camps and government actions against Japanese Americans during WWII.

Subjects & Topic:After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941 and the U.S. declaration of war, 80,000 thousand American citizens of Japanese ancestry, and 40,000 Japanese nationals, who were barred from naturalization by race, were imprisoned under the authority of Executive Order 9066 in War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps. There were approximately 11,000 people of Japanese descent, who were actually interned following a recognized legal procedure and the forms of law. They were citizens of a nation against which the United States was at war, seized for reasons supposedly based on their behavior, and entitled to an individual hearing before a board. Whereas, the 120,000 Japanese and Japanese American men, women, and children in the WRA camps had no due process of law and this violation of civil and human rights was justified on the grounds of military necessity.

Within four months of the Executive Order, all persons of Japanese descent had been removed from the western portions of California, Oregon, and Washington to supposedly protect against sabotage and espionage. While some Italians and Germans were imprisoned in the U.S., they posed no threat on the west coast and faced nothing like the racial animosity borne by the Japanese. Without any due process, Japanese families were forced to leave their homes and sent first to Temporary Assembly Centers and then routed to any of ten hastily constructed War Relocation Authority camps located on large tracks of federal land in remote areas of the western United States far from strategic areas. The camps were built from scratch of wooden barracks with tarpaper walls surrounded by barbed wire fences and guard towers. The unsatisfactory living and working conditions were communal with little privacy and minimum comforts in extreme climates.

By October of 1942, the WRA began to develop leave clearance procedures to enable about 17,000 Japanese American citizens (majority 18-30 years-old) to re-enter civilian life as students or workers (about 7% of the total number of Japanese American incarcerees). The WRA reviewed their loyalty, prospects for self-support, and the reception of the community where they intended to move, the majority went to Chicago, Denver, Salt Lake City, or New York, far from their west coast birthplaces.

Then in early 1943, the War Department developed a questionnaire to identify possible military volunteers and the War Relocation Authority decided to use it to identify incarcerees who might be released from the camps. Called the “Application for Leave Clearance,” it was distributed to all the WRA camps to determine the loyalty of the incarcerees. The “loyalty questionnaire” was given to all Japanese Americans age 17 and over in the War Relocation Authority camps. Two clumsily worded questions caused confusion and consternation. Refusal to complete the questionnaire, qualified answers, or “no” answers to a question about serving in the armed forces (number 27) and foreswearing allegiance to the Japanese emperor/foreign governments (number 28) were treated as evidence of disloyalty. These questions resulted in a great deal of outrage and controversy. Japanese American citizens (Nisei) resented being asked to renounce loyalty to someone who had never been their Emperor. First generation Japanese Americans (Issei) could not gain U.S. citizenship, thus renouncing their Japanese citizenship would leave them stateless. Asking people to assume stateless status is a violation of the Geneva Conventions governing the treatment of enemy aliens. Those who answered “no” to one or both of the questions were designated as “disloyal” to the U.S. The spurious nature of these two survey items, led to these questions being hastily rewritten, but the damage was done.

This loyalty review program was the most divisive crisis of the incarceration and led to the transformation of the Tule Lake camp into a high-security Segregation Center to house those who refused to register or answered the loyalty questions “no-no.” This meant that about 12,000 “disloyals” and their families were transferred to Tule Lake, which required that 6,500 people already living in the Tule Lake WRA Camp were to sent to other WRA camps to make room for them. About 6,000 pre-segregation people decided to stay in the transformed Tule Lake Segregation Center so as to not be separated from their families or for other practical reasons. Tule Lake became a trouble spot with this mixture of “disloyals” from various WRA Camps and there were conflicts, not only with the camp keepers, but within the community.

Security at Tule Lake was increased with military police, a jail, a stockade (prison before jail built in 1944), and fencing to turn it into a maximum security facility, all of which contributed to the turmoil. The segregation turned Tule Lake into a very complicated place with factions forming such as Hoshi Dan, a Japanese nationalist group. A work stoppage after a farm truck accident in which 29 people were injured (5 seriously and 1 died), escalated into a strike and a series of events that led to the Army declaring martial law and taking over the camp. Repression, imprisonment, shortages, and other hardships were endured while disillusionment grew as draft notices began arriving. Only a total of 1,256 people volunteered for service from all the WRA camps, whereas over 10,000 volunteered from Hawaii alone (where people of Japanese descent were not incarcerated).

Those segregated at Tule Lake were caught in a situation where Japanese nationalism offered a positive alternative, further dividing the camp population. Many immigrants and citizens determined that it was possibly safer to be “repatriated” to Japan rather than stay in the U.S. The concept of giving up United States citizenship, though shocking to some, was a choice of serious consideration and implications. Many feared for their safety in hostile white communities if they were released from the camps before the war was over and so thought Japan would be safer than the U.S. Others were outraged with their imprisonment and disillusioned. Renunciation was made easier by an Act of Congress, the so-called Denaturalization Act of 1944. Initially, fewer than two-dozen Tule Lake incarcerees applied to renounce their citizenship, but when the WRA announced that the camp would close in a year, panic and confusion ensued resulting in 7,222 (1/3 of the Tule Lake camp population) Nisei and Kibei renouncing, 65 percent of whom were American-born. In contrast, only 128 people from the nine other WRA camps renounced their American citizenship. Ultimately, many were repatriated to Japan, while others who signed up to go to Japan realized it was a mistake. Wayne Mortimer Collins, a Civil Liberties Attorney, prevented the Department of Justice from deporting en masse the people of Japanese descent who renounced their U.S. citizenship. But the effort to restore citizenship took 22 years—eventually nearly all, except about 40-50 people had their citizenship restored.

Tule Lake became the largest of the WRA camps with 18,700 incarcerees, although it was built for 15,000. Within the microcosm of Tule Lake, the complexity and consequences of the Japanese American WWII incarceration was played out on the most dramatic of stages. The Tule Lake Segregation Center was the last of the WRA camps to close on March 20, 1946.

For a more in-depth discussion with illustrations and summary tables, see Appendix A, and/or the timeline in Appendix B.

Content StandardsCCSS.RH 2. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

CCSS.RH 6. Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, and evidence.

CCSS.RH 9. Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

NCSS.D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

NCSS.D2.His.2.9-12. Analyze change and continuity in historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

NCSS. D2.His.12.9-12. Use questions generated about multiple historical sources to pursue further inquiry and investigate additional sources.

NCSS.D2.His.14.9-12. Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

NCSS.D2.His.15.9-12. Distinguish between long-term causes and triggering events in developing a historical argument.

NCSS.D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

PreparationArchival materials used throughout this lesson are made available through the California State University Japanese American History Digitization Project (CSUJAD).

Use the CSUJAD exhibit “Before the War” to learn about the lives of Japanese Americans in the United States prior to the outbreak of WWII. Students can also use the background reading assignment (Appendix A) and the timeline (Appendix B) to establish a context for why these camps were created and how the U.S. Government justified their need during WWII. Include President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order no. 9066 that authorized the relocation of Japanese Americans within this background history.

Lesson ActivitiesWhat does it mean to be loyal? Do circumstances matter when determining whether to remain loyal? Using Merriam Webster's online dictionary, discuss the meaning of the words “loyalty” and “loyal" and examine the importance of context when determining what loyalty entails.

Considering what was covered in Appendix A (Background Reading) and Appendix B (Timeline), what might it feel like to be a Japanese American who was required to complete a loyalty questionnaire after having been in a War Relocation Authority camp for a year? Review the "loyalty questionnaire” available at CSUJAD before discussing the following questions:

After reviewing the different types of camps used during WWII and which U.S. government organizations administered them (Appendix C), explore the Densho Encyclopedia to learn about the various sites of WWII incarceration in the U.S. D iscuss the differences in the camp populations and treatment of the prisoners (working conditions, security, detention facilities, etc.) with the following questions:

Students work with photographs and letters from the camps made available through the CSUJAD database. Students can be assigned one subtopic and then brought together with students responsible for the other topics to discuss their findings, or students can be assigned each of the subtopics within this activity. When working with the primary sources, students can also access the "Terminology Differentiating People of Japanese Ancestry" (Appendix A) and "6 C's of Primary Source Analysis" (Appendix E).

An information card indicates that Toshio Kuratomi, 28 years old, was moved from San Diego via the Jerome, Arkansas WRA Camp to Tule Lake. Analyze the intake photographs of Kuratomi and Mitsuho Kumra that were taken during their transfer to Tule Lake from other War Relocation Authority Camps and compare them with what you have learned about the camps thus far.

The three photographs below show different elements of what living in Tule Lake was like. Notice the dates that the pictures were taken and look at the Timeline (Appendix B). Consider the transition of Tule Lake from a War Relocation Authority Camp to a Segregation Center.

In December of 1944, before the war was over, the War Relocation Authority announced that the incarceration would end and the camps would close within a year. There was much confusion in the camps about where the incarcerees would go and anxiety about the safety of people of Japanese ancestry once released. At Tule Lake, 7,222 Nisei and Kibei renounced their citizenship thinking it would be safer for their families to be in Japan, whereas only 128 from all the other WRA camps renounced. The effort to restore citizenship took 22 years in U.S. courts.

Read Tsugitada Kanamori’s written declaration, given under oath, that provides extended background information to support cancelling his renunciation and reinstating his U.S. citizenship. (U se the expansion button with arrows in the upper right corner of the image to see the entire document).

In this letter from Aiko Takaoka, sister of Yoshio Takaoka, she request news about her brother’s safety and a release from the Tule Lake Stockade (prison before the jail building was built) from the Camp Director, Raymond Best.

After completing the lesson, have individual students, or groups of students working together, search and use archival materials in CSUJAD t o participate in the following activities:

Students should research and create an investigative report to communicate to the American people news about what the conditions were like in the WRA camps during WWII. Use the CSUJAD online historical archive images, text, etc., to build and illustrate the story. They can then download and share the archival materials discovered to support their views and create a type of digital storyboard or narration using Google slides and speaker notes, MS Powerpoint, or other presentation tools.

Have your students write their official U.S. representatives, in Congress or the Senate, a letter expressing their views on the incarceration of people of Japanese descent during WWII. Have them pretend that it is 1943 after the loyalty questionnaire has been distributed and people in the camps are being drafted for military service. Encourage them to share actual quotes from the people who were in the WRA camps, use images, or any other archival information from the CSUJAD project. An illustrated letter can be created using Open Office, MS Word or other word processing tools.

If your students are still developing primary source analysis skills, Appendix E provides a tool, called the 6Cs of primary source analysis, to guide their analysis of any given archival object. When using the CSU Japanese American Digitization project to find archival materials to analyze, see also Appendix D, which provides a guide to assist with effective searching of the database.

By the end of the lesson, students should be able to write brief responses (1-2 paragraphs) or a longer essay (1-2 pages) about the following questions:

Have students search the CSUJAD online database of archival objects to find primary sources that further illuminate the issues associated with the loyalty questionnaire and events/conditions at Tule Lake Segregation Center (User Guide - Appendix D).